Faith47 made her mark on the streets as one of South Africa’s most recognisable graffiti artists. Now, years later, Faith XLVII’s work lives not only on walls, but in museums and galleries around the world. Currently, her latest exhibition Venarum Mundi is showing at Heron Arts in San Francisco.

For Women’s Month, we’re catching up with the artist — born Liberty — whose journey from painting city streets to showing at institutions like the Brooklyn Museum speaks to a career defined by evolution.

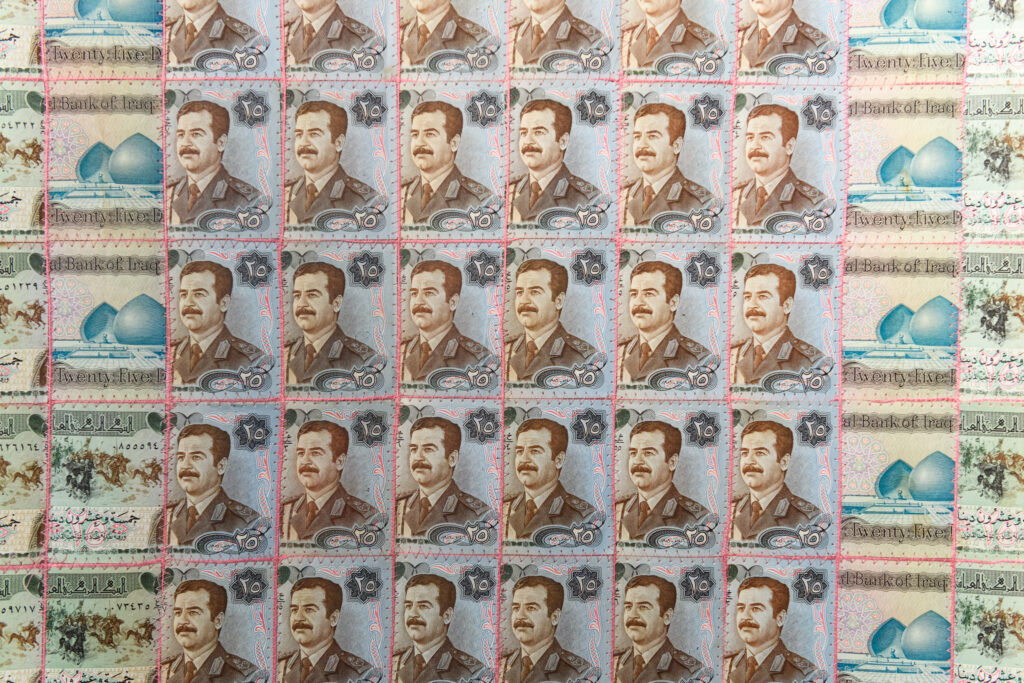

Her latest exhibition, Venarum Mundi at Heron Arts in San Francisco, continues that shift. Using obsolete banknotes, vintage maps, and hand-sewn textiles, she pulls apart the systems and borders that shape our lives, then stitches them back together in works that are both delicate and monumental.

At its centre is The Nature of Memory, a large-scale indigo and madder-root textile that calls back to the colours of ocean and sky. It’s a work about connection, migration, and our place in the natural world, and a reminder of how women artists continue to reshape global narratives through their craft.

Tova Lobatz spoke to Faith about the sacred and the systemic, her Cape Town collaborators, and the personal shifts shaping this new chapter of her work.

‘Venarum Mundi’ translates to ‘Veins of the World.’ How does this title reflect the emotional and political currents of the exhibition?

The title acts as an entry point into the exhibition, the substrates are built from the scaffolding of our world: currencies, maps, flags. They give us a sense of represented structure to the political and national identities we have constructed. Then also weaving in the elemental forces of the planet itself.

Your use of obsolete currency and vintage atlases reads like a poetic indictment of global systems. What draws you to these materials?

My practice embraces assemblage; repurposing obsolete, discarded, found objects to bring about new meanings. When I look at discontinued currencies and outdated maps, I see an inherent aesthetic beauty that speaks to a deeper thread of how we place value and meaning in the world.

You frequently operate at the intersection of the sacred and the systemic. How does that tension show up here?

That’s an interesting observation and it makes me reflect on my psychology which I think has been at times informed by an instinctive push away from the dogma’s of modern society, and a deep pull towards the sacred. These days I am focusing more on the pull towards the sacred, then the push from what doesnt resonate with me. That aligns more. But it’s a journey to learn what doesn’t resonate, and to align with what does. In this body of work. I guess one could say that the breaking down of the objects themselves is the literal cutting down / dissecting of human constructs, and then the sewing and threading back together of elemental forces then becomes the spiritual metaphor and the creation of beauty. The creation of beauty is something intrinsic to us all.

The tapestries are incredibly intricate. Tell us about your creative process: how does an idea become textile?

It’s deeply collaborative. To bring these ideas to life, I work with my friend Clare Heron (a lingerie designer), and a team of seamstresses in Cape Town who specialise in quilting and streetwear, my nieces, my sister. The result is a nuanced back-and-forth dialogue between my vision and their craftsmanship.

How do you source materials like banknotes and maps? Why Originals over reproductions?

I’m constantly hunting for original ephemera; banknotes, atlases, vintage maps. With the Zimbabwean notes I ask Zimbabwean friends visiting home to collect for me and source others online. Original artifacts carry a tactile storied history that resonates energetically and texturally through objects.

How does physical space shape your installation strategy—whether site‑specific or mural?

Every project starts with listening to the space. There is a conversation between how you walk through a space, the texture, light, and flow. All of that is necessary to feel into in order to speak with and to envision a work that can feel like it naturally / timelessly exists in a space. Be that installation in a museum, or a painting in a neighborhood.

Tell us about the site‑specific aspects of Venarum Mundi. How does context—urban, political, geographic—influence the work?

With this installation I was able to step into something new. A kind of abstractive representation in a pure, stripped down form. The nature of memory, could also be titled the memory of nature, as is calls to the innate cellular memory that we hold of the natural world.

The mediums used, natural silks and calico, indigo and madder plant dyes – they are important. And the simplicity of form is important. The structure of the simplest geometric shapes and gradients asks us to reach into our selves and walk the bridge that is so severed – of the connection to the natural world, and to awaken our archetypal knowing.

This installation took months of testing and traditional VAT dying by Mary Ralphs in Cape Town to get to the perfect tones.

How do you balance political engagement in your work with poetic ambiguity?

I’m not too interested in political messaging these days, im more interested in what moves inside us. That is the world that I find the most fascinating, mysterious and luminous. From that space the world can change around us right?

Poetic ambiguity – ambiguity being important. We need to feel tension, a sense of awe, an intrigue. Because there is so much that we don’t understand. And when we can approach life and art from that basis, of humility, then we have a good chance at making work that is honest and can resonate with the fragility of what it means to be alive.

Your work feels deeply personal even as it speaks to collective themes.

Well, yes because the personal and the collective are not separate, just like we are not separate from nature. We are all threaded together.

How has your worldview evolved from earlier work, and how is that reflected here?

There s a juxtaposition that is happening in the map tapestries specifically, where you will find locations for instance Sri lanka or Johannesburg next to a river near Wuhan or Kinshasa. A repositioning of space, cutting down of borders. Then there is also the repositioning of land, mounting ranges all gathered together in a gradient reaching to sky. Or tapestries that have been made from icecaps and oceans. Reassembling the elements and the topography of earth.

In the currencies we’re seeing national symbols or pride and identity side by side – randomized in seemingly chaotic balance. The threads themselves become an expression of interweaving and joining.

These works hold and witness the world we live in from different angles.

What do you hope viewers take away from Venarum Mundi intellectually, emotionally, or spiritually?

I hope they feel a simultaneous sense of expansion and intimacy: an awareness of the land beneath our feet, and how that land spreads in all directions and holds up all of life.

What’s next for you creatively? Are you exploring new mediums or themes?

I’ve shifted back to South Africa to foster a more intimate art practice one that can embody rhythmical meditative, dreamlike, ritualistic practices. I’m threading psychological alchemy and subconscious imagery into everyday living. I want to make nature-based, totemic somatic work.

In April 2026 I’ll present Solor Logos—a deeply intentional extension of this path. The Nature of Memory installation signals this trajectory.