Favianna Rodriguez, an interdisciplinary artist, cultural strategist, and entrepreneur based in Oakland, California, is in South Africa for the Global Artivism Conference, which takes place in Pretoria from 5-8 September. Read on to gain insights into her journey, creative activism, and vision for a just and equitable future and to see some of her beautiful art…

The Global Artivism conference, in partnership with the Riky Rick Foundation, explores the dynamic intersection of arts and activism, highlighting the pivotal role of creative expression in advocating for societal and environmental change. Favianna is one of many international and local thought leaders and artists who will share their work and thoughts at the conference.

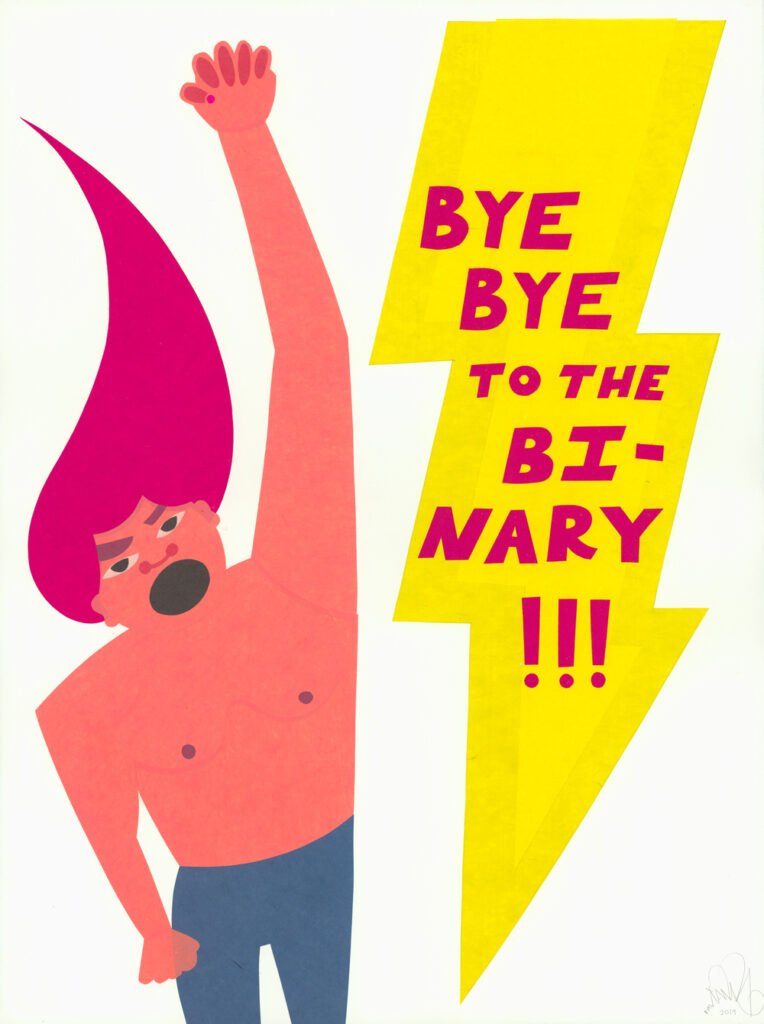

Favianna Rodriguez’s art often addresses themes such as migration, gender justice, climate change, racial equity, and sexual freedom. She is the President and founder of The Center for Cultural Power, an organisation igniting change at the intersection of art and social justice in the United States. This is what she had to say…

Artivism for Safe Spaces” is a powerful theme. Could you share your vision of what constitutes a “safe space” in the context of artivism, and how do you ensure your work fosters these spaces in communities?

To address this question, it’s essential to recognize that dominant culture often benefits privileged groups—typically white, wealthy, able-bodied, straight men—while leaving many voices unheard. To create inclusive and safe spaces, we must uplift marginalised communities and challenge these dominant narratives.

This involves embracing and elevating the experiences of people from the global majority, Indigenous communities, Black people, LGBTQ+ individuals, people with disabilities, and immigrants. By amplifying diverse stories, we foster deeper connections and understanding, making spaces genuinely safer and more inclusive.

For example, anti-immigrant narratives can lead to violence and discrimination as we recently saw in the UK, but fostering a culture that values immigrants creates a safer environment. As an artist, my role is to uplift these suppressed stories, including my own, and actively contribute to this narrative shift.

Your work is heavily focused on the concept of the “radical imaginary”—imagining new futures rooted in equity and justice. How do you believe the radical imaginary can transform communities, and how can artists contribute to this transformation?

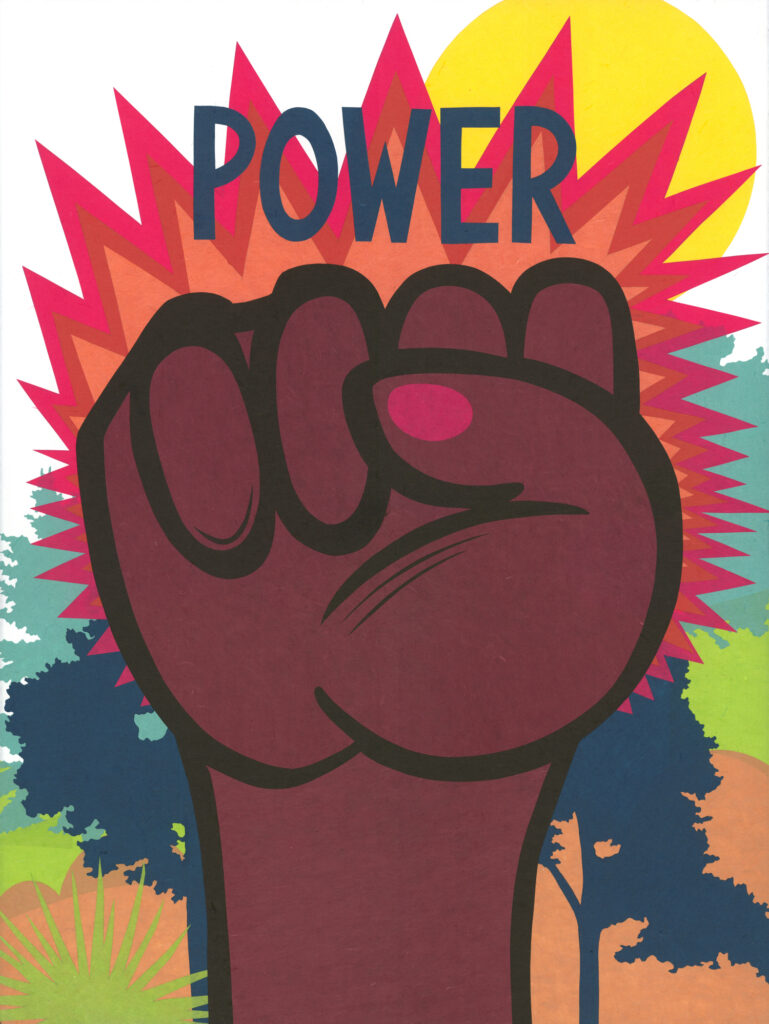

The radical imaginary envisions a world where everyone thrives in harmony with nature, contrasting sharply with today’s reality of extreme wealth inequality, ongoing militarism, climate crisis, and systemic anti-Black and anti-Indigenous policies. This vision aims for a world where safety and equity are universal and divisions no longer hold power.

Futurism and imagination through the arts—film, theatre, music—allow us to express and realise these values. Artists can transport us to a world with greater equity, making it feel achievable. For example, envision a world where young girls are free from gender-based violence and see themselves in diverse roles like doctors and astronauts. Art that evokes empathy and moves us emotionally can inspire action, making artists crucial in shaping and striving for a transformative future.

Intersectionality is a significant aspect of your work. How do you address the complexity of intersectional identities (gender, race, class, etc.) through your art, and how do these issues connect to your activism?

Intersectionality is incredibly important in my work. The reality is that certain groups of people have historically been more exploited, violated, and murdered than others. These bodies often belong to those from the African diaspora, Indigenous communities, women, and now increasingly, the trans community. Low-income individuals have also suffered more than those from wealthier classes. All these issues are interconnected because, in reality, what we are witnessing is the result of over 500 years of racial capitalism, which has enabled the exploitation of certain bodies to concentrate wealth and power in the hands of a dominant, wealthy class.

We often think these issues are complex, but at their core, they are not. It boils down to narratives and cultural norms that have allowed for the subjugation of certain people. Policies rooted in these narratives have perpetuated this subjugation. Ava DuVernay’s recent film, Origin, has brilliantly highlighted how deeply ingrained these issues are, and it is crucial that we challenge the core narratives that have allowed these injustices to continue.

For me, intersectionality is key because it helps us connect the dots. When we discuss issues in isolation, we miss the broader picture. A fundamental value I hold is that every human being, regardless of their country of origin, race, or gender, should be able to thrive in this world. They should have access to healthcare, shelter, and the ability to see themselves reflected in popular media.

In my art, I always strive to tell intersectional stories because our experiences as people are inherently intersectional. My experience as the daughter of immigrants, as a woman of color, as a queer person, and as an American is unique. Through intersectional storytelling, we can connect the dots on the issues that affect our lives. This is crucial because politics often tries to silo issues, but in reality, these issues are deeply interconnected.

Your work frequently explores the intersection of art and social justice. How do you approach blending these two areas, and what challenges have you faced in using art as a tool for activism?

All art reflects a specific point of view and is inherently political. Despite this, we’ve been led to believe that art by white European men is superior to that by other cultures, especially Black and Brown artists. Recognizing which art is uplifted versus marginalised is crucial.

Art intersecting with social justice often stems from personal experiences of injustice, such as growing up in polluted areas or facing systemic inequality. This art isn’t merely political; it offers perspectives that haven’t been normalised.

Blending art with social justice means creating work that aims to change hearts and minds. Art’s emotional power can challenge views on war and climate change, driving significant impact. My goal is for my art to educate, mobilise, and provoke action.

Systemic challenges include the dismissal of art activism as merely “political.” Despite this, I’m committed to creating spaces for transformative work and supporting other artists in this crucial endeavour.

You’ve been deeply involved in environmental justice and have created art around climate change and ecological sustainability. What impact do you hope your art will have on global conversations around climate justice?

I’m deeply passionate about the environment because I grew up in a polluted community in Oakland, California. Through my studies of history, I’ve come to understand that oil companies have long targeted the poorest communities, particularly communities of color, around the world. These companies have not only destroyed ecosystems but have also murdered leaders across the African continent who stood up to them, as well as Indigenous people in my homeland, the Peruvian Amazon, and throughout Latin America. The climate crisis is not just a result of industrialization; it is rooted in colonialism. This crisis began in 1492, when colonisers arrived and started to pillage the land, destroy ecosystems, and exploit resources. We are still paying the price for that today.

My hope is that we can shift the conversation about climate change away from a purely scientific lens and start to understand that climate change is deeply intertwined with racial and gender justice. I want to break open these conversations because they often overlook the root cause: racism and colonialism. My goal is for the climate movement to recognize that we won’t achieve meaningful progress unless we centre the stories and voices of those most affected. The climate crisis is overwhelming and often painted in doom and gloom, so we need artists to help us find hope and to heal our relationship with nature.

Through my art, I want to help people see the climate crisis from a different perspective. I aim to give people the tools to grieve, reflect, organise, and recognize that it’s not too late—we can still make a difference.

Identity and migration are themes that permeate much of your work. Can you talk about how your own background has influenced your creative activism, and what advice you would offer to other artists from immigrant backgrounds?

As a first-generation American who grew up in an immigrant family, my background has deeply influenced my creative activism. My family was mixed-race—my father was Afro-Peruvian—and our immigrant experience was shaped by the fact that my ancestors faced discrimination in their homeland. They came to the United States during a time when harsh policies against immigrants were being enacted. Growing up, I was acutely aware that the dominant narratives surrounding immigrants were harmful lies that led to destructive policies.

Migration is a human right. Human beings have been moving across this planet since the beginning of time, and borders are a man-made construct. In my case, the need to migrate was driven by historical exploitation. The United States, along with colonial powers like Spain and France, looted resources, committed genocide against Native peoples, and initiated the Transatlantic slave trade in what is now known as Latin America. They accumulated wealth through exploitation, death, and land grabs, leaving many people in poverty. My parents had to immigrate for economic opportunity, a direct result of colonial actions.

There’s often a misconception that immigrants come to take resources, but in reality, the true resource-takers were—and still are—the global powers that enriched themselves at the expense of others. I’ve always known this to be true because I witnessed how hard my parents worked and how this country exploited them. Through my art, I want to tell these stories and help create a world where immigrants can be safer, where the root causes of immigration are understood, and where we support reparations for the harm that the United States, in particular, has caused in other countries.

To other artists from immigrant backgrounds, my advice is to embrace your connection to your homeland and your identity as a driving force in your artistic work. You have a unique perspective that allows you to bridge cultures, and your stories are essential. We need to hear from those who have been on the move or whose ancestors were on the move, especially as climate migration becomes an increasingly urgent reality. Your perspective is crucial in helping us adapt to the future.

As a cultural strategist, you work beyond the canvas and into larger movements. How do you collaborate with activists and organisations to ensure that your art is not just expressive but also effectively contributes to systemic change?

I collaborate with global social movements to ensure my art drives systemic change. Art gains power through partnership with movements fighting for climate, gender, and racial justice. By maintaining strong ties with activists and organisations, I align my art with their solutions and reflect their strength.

Effective change requires engagement across cultural, political, and economic realms. My art advances narratives that support policy shifts and real power. I also build institutions and address systemic injustices affecting marginalised artists by creating a national organisation that trains and supports them – The Center for Cultural Power. Cultural change precedes political change. To achieve real power and systemic change, culture must be a central part of the strategy.

* Catch Favianna in action during the Global Artivism Conference, where she will be leading discussions and sharing her work. You can find more information on the event’s website and discover how art is being used as a powerful tool for social justice and change.